Article

Focus

Rodin's imprint on Britain.

In July 1915, three years before his death, Auguste Rodins sculpture The Burghers of Calais,bought by the National Art Collections Fund in 1911,was quietly uncovered in Victoria Gardens by the Palace of Westminster. This was the first major acquisition of Rodins work by a British organisation and the third of eight works to have had funding by The Art Fund. After recent Art Fund restoration in 1999, the sculpture still stands in its position that resonates with history. Today this is not only about the work’is symbolic association with the site, but represents the history of a French artist who had a truly special relationship with Britain.

Auguste Rodin (1840- 1917) is often considered to be the pioneer of twentieth century sculpture. His departure from traditional and classical sculpting methods, to a style that focused on texture and light, made him the most daring and innovative sculptor of his day. If, during the last autumn you had visited Victoria Gardens to view the monument, you would have been disappointed to learn that the sculpture had been temporarily moved. Fortunately this was because it was part of last autumns major Rodin retrospective at the Royal Academy. It represented the first Rodin exhibition in Britain for twenty years, displaying three hundred works, many of which were being shown outside France for the first time. Ten chronological themes explored every aspect of Rodins work from his public sculpture and smaller-scale pieces to his drawings and interest in antiquities. However, perhaps more importantly, it was an opportunity to view pivotal works of art that the Art Fund has helped collect and thus see the part the organisation has played in maintaining the admiration of Rodin in Britain. Two works in the show The Kiss and The Burghers of Calais, are widely considered to be two of the artists finest examples and because of The Art Fund we are fortunate enough to have them in our public collections.

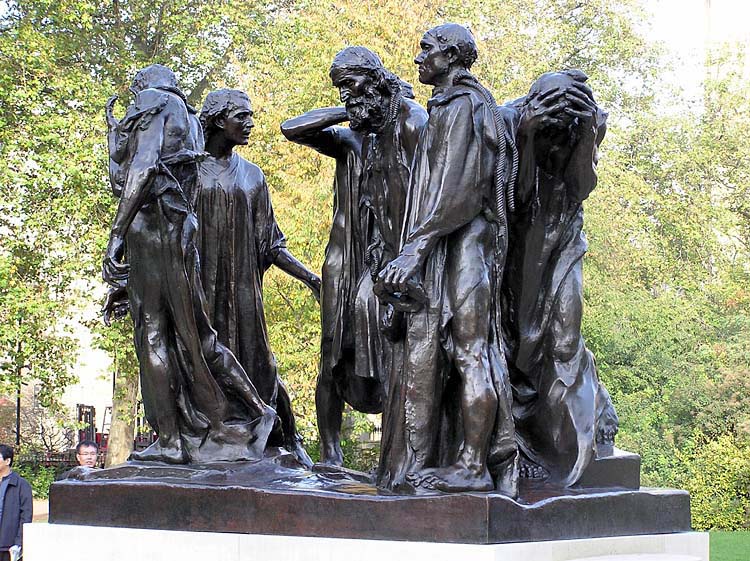

The Bughers of Calais, Bronze, 1884- 1895

The Bughers of Calais, Bronze, 1884- 1895

Cast 1907- 1908

ArtFunded 1911 (£2400)

This is just some indication to suggest why The Art Fund has taken steps to acquire works of Rodin. Despite his celebrity status, it was needless to say his artwork that spoke for itself. As one wandered through the exhibition rooms of The Royal Academy, his free- standing figures were succeeded by the first of two major works at the exhibition. In the centre of the room stood The Burghers of Calais (1884-1895). The origin of this masterpiece was a commission from the mayor of Calais who in 1884 approached Rodin about the prospect of creating a monument in memory of the citys medieval hero, Eustache de St- Pierre. Rodin dismissed old practice of public sculpture and rather than depicting just one figure decided to show all six burghers, who in 1347, having been under siege for eleven months opted to sacrifice themselves. In return King Edward III would spare the city. The piece resides around the moment when each burgher realises his commitment to death as they leave their city carrying the keys to the English King. Nothing about the sculpture is conventional; the hands and feet of figures are disproportionately over-sized suggesting a sense heroism and vulnerability. Also the figures positioning neglect any sense that the figures are aware of eachothers presence. This in particular undermines the naturalism of the work but emphasises Rodins effort to identify with his subject to such an extent. These elements, together with the figures powerful expressions and gestures conform to show a powerful scene of courage and pathos. Fundamentally the piece recognised Rodins determination to break the conventions of public monuments, in terms of composition, meaning and installation. This made the gothic architecture of the Houses of Parliament (a site Rodin himself intended the sculpture to stand) an appropriate setting for the cast (cast 1907-1908) that the National Art Collection Fund bought for the sum of £2,400 in 1911. It was one of twelve bronze casts made of the piece measuring 210 x 232 x 178cm with the original being inaugurated outside Calais Town Hall in 1895.

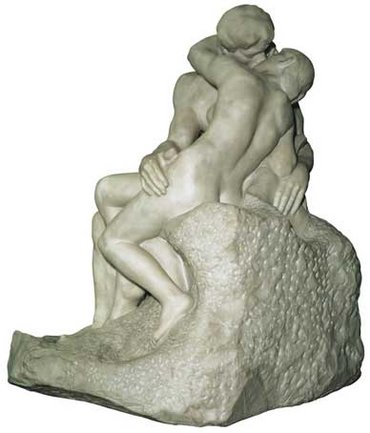

The second of these two pieces was found in the adjacent room, again placed in the centre on a high plinth as if to show its authority among the works. This continued the momentum of the exhibition, that each room was followed by the next with another ‘ showpiece work in the centre. The Kiss (1901-1904), made from Pentelican marble was purchased by The Tate in 1953 with a £2,000 contribution from NACF. The story from which it is taken only emphasises Rodins effort to portray something so powerful and beautiful, yet tragic. Originally intended for The Gates of Hell (also displayed at the exhibition) the piece depicts a scene of Paulo and Francesca from Dantes poem Inferno. The young couple lived in Italy in the thirteenth century, and fell in love whilst reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere. As their passion grows and they exchange their first kiss they are caught by Gianciotto, Francescas husband who stabs them both to death. In 1883 when William Henley received photographs of the piece and in a subsequent article written on his behalf Julia Cartwright wrote that nobody had ever surpassed Rodin in the representation of the very instant of the kiss, and that with such union of purity and passion, of lofty art and intense humanity, as places his work on a pinnacle apart. More recently a poll for Classic FMs listeners in November 2003 established that The Kiss was the nations favourite masterpiece out of works collected by the NACF. Viewing it on its high plinth at the RA gave no suggestion that the result would be any different three years on. The viewers attention was occupied as soon as they walked in the room by the piece that is generally considered to be one of great images of sexual love in art. It is one of three over-life sized versions made in Rodins lifetime, measuring 182.2 x 121.9 x 153cm and weighing 3180 kg. The form of the lovers emerges from the highlights and shadows of the statue which helps generate a real impression of human presence. Once again the disproportionate hands and feet, exaggerated muscular tones and intensity of the kiss make it an idealistic pose of eroticism and love. However romantic or emotional the work seems to be it is still sculpture. It doesn't go over the top and his traditional notion of using energised form suitably balances with his ability to let the work become impressionistic in his choice of subject, style and medium of which The Kiss is perfect example.

The Kiss (The Tate), Marble, 1901- 1904

ArtFunded 1953 (£2000)

The nation is fortunate that The Art Fund has acquired such examples for its public collections and thus have on view Rodins work to the public. This has no doubt had influence over the work of British contemporary sculptors. In light of the recent exhibition, Royal Academicians Antony Gormley and Anthony Caro have spoken about Rodins influence today. Gormley refers to a work exhibited in the show called The Age of Bronze; a sculpture Rodin donated in 1914 and a cast of which The Art Fund helped Leeds City Art Gallery obtain in 1994. It was Rodins first large sculpture and Gormley mentions that it relates so extraordinarily to the whole history of the western school of sculpture, as it is simply about a naked body in space. Further he sees a link with another contemporary sculptural interest that is the connection between subject and material, which in this case is between bronze and the uncertainty of the nude figure. Similarly Anthony Caro notes that Rodin started off so many things that today sculptors do; it took years for us to realise that if you took parts and put them together you could make new sculpture, and you could vary things and change heights. The penny didn't drop for years about Rodins possibilities. He sees Rodin as the first person to put life and emotion into sculpture and in particular mentions The Burghers as being the first sculpture to incorporate it. He says the work could be on the ground or could be very high and they become two completely different things: either they are something that you relate to like another person, or they are something up there that you look up to and respect”. In this way both sculptors are asking the same questions in their own work as Rodin was a century ago.

It goes without saying that without works such as The Kiss and The Burghers in our collections then there wouldn't have been so much read into the work and practice of a man that heralded the modern age of sculpture. In this sense The Art Fund can feel partly responsible for his admiration in Britain. This shows the benefit organisations like The Art Fund have on our public collections and further illustrates more than ever, the need for organisations to work with museums and galleries to obtain high profile works. Not only do they promote the status of our galleries and museums but also increase educational opportunities and prospects of aspiring artists. Rodins place in our galleries cannot be questioned and can only be made more prominent.

Abstract

Proposal