Review of ‘PLAY’ exhibition by BEARSPACE Gallery at the Cello Factory, Cornwall Road, Waterloo, London

Plus+ Interview with Jock Mooney

1st

– 4th November – open to the public, 12.30-5pm

5th – 16th November – by appointment only

Hidden away, set back from the road and on a street where the numbers don’t follow numerically makes this exhibition quite hard to find initially. Nestled just off London’s south bank amidst the arts and cultural giants such as TATE, Hayward Gallery, BFI &etc… This latest offering from BEARSPACE gallery, found in their temporary one show only location at the Cello Factory in Waterloo is well worth hunting for. Why venture to visit the low key event of BEARSPACE against the latest sensations elsewhere? Quite simply, in the next ten years it will be these artists the crowds will be queuing to view at big name venues elsewhere. Occupying this show are fresh, young, exciting artists (as well as some more established) and undoubtedly there is something splendid about discovering such a special gem like this that is personally satisfying.

On show is a collective of 17 artists, some collaborative, whose nationalities include Japanese, American, English and Scottish. These like minded contemporary artists have been brought together by the refreshingly energetic young curator Julia Alvarez. “BEARSPACE tries very much to reflect a certain zeitgeist or current philosophy” , Alvarez admits. The exhibition offers works by emerging artists and more established successful artists the like of Anya Gallacio and the Chapman Brothers. The overall collective ethos of the show seems to ring out as something akin to the European Dada of the early twentieth century, with an over crowded opening night to match. The teasing nature of these rebellious works form a spirit which may come to be seen as a New Wave Dada for the 21st century, the prospects of which invigorate imaginations and capture glimpses of life in the digitally mediated age we live. But is the underlying methodology of this exhibition as radical in its delivery as Alvarez sees it?

The show is a sophisticated look at play and as Alvarez notes, “the artists that we show have past into adulthood and obviously they are able to look at play in a more subjective way, perhaps draw out child hood memories to look at culture and how play can often be related to darker activities and vulnerabilities”. No longer innocents and certainly not naive these artists reflect on youth. The artists’ here present works as homage to youthful play, nostalgically referencing childhood exuberance and teenage angst. The show is also ahs an element of play for the senses. The visual stimulation of Doug Fishbone’s video work and Jock Mooney’s sculptures, the delicacy of touch and feel is gifted by Bob and Roberta Smith’s wall installation, while the nuances of sound and hearing are tuned out by Neil Zakiewicz. As for the sense of taste on offer, the opening night saw the little artists (famous for creating quirky Lego reproductions of contemporary artists and their works) provided refreshing ice-lollies in the form of Marc Quinn’s ‘Blood Head’. Made of strawberry flavouring, some might consider them dis-tasteful but these tiny ice replicas on wooden sticks were an undeniably delicious taste to savour as accompaniment to sensually experiencing the whole show. But what of the smell? The lively space was odourless all except for an air of amusing excitement that scented the gallery arena. In interview Alvarez reveals “I do like to look at how humour is utilised in art, I think it’s quite an interesting discourse around it”

Spanning two floors, the show is presented throughout three rooms of various art media. And with two staircases it is possible to endlessly run around the space like roaming through an adventure funhouse that shares a raucous order akin to the feel of a noisy school playground!

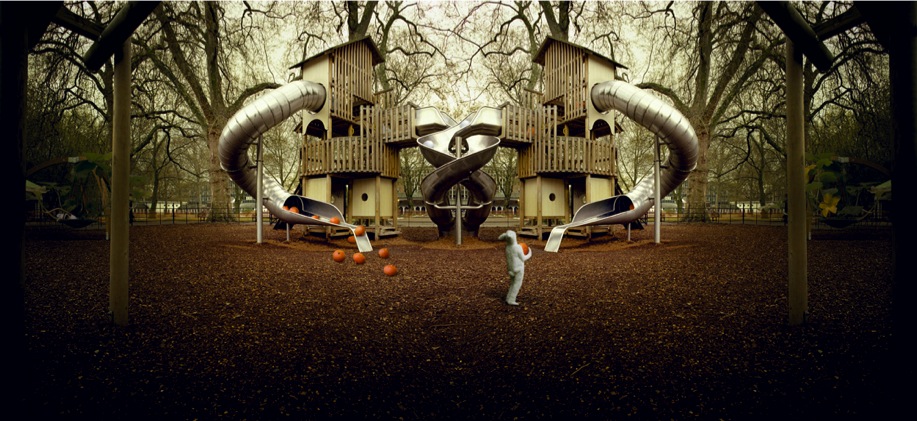

'An endless Pumpkin Machine', Toshie Takeuchi (2005)

Four of the artists

in this playground like show are represented by BEARSPACE, and Toshie

Takeuchi is one of them. From the childhood nostalgic imagery evident

in Takeuchi’s work one can see exactly Alvarez’s reasoning

for her inclusion. Her works are often inhabited by imagery of children

in rabbit costumes in an eerie nightmarish scenario. The playful darkness

of her photographic manipulations brings to mind the strangeness of children’s

literature by Maurice Sendak that makes the work linger nostalgically

with childhood memories. The main structure within Takeuchi’s

panoramic piece ‘An endless Pumpkin Machine’ is a mirror image

of a twisted slide adventure playground hut that resonate a sinister touch.

The pumpkins rolling out from within the imposing chrome contraption housed

under the tall bare branched trees surrounding evokes an unnerving sight

the likes of a Hitchcock movie. And in the foreground is a child dressed

as a rabbit carrying a pumpkin which echoes the advent of Halloween. The

success of Takeuchi’s digital montage is how the images stage a

fine subtle play in creating a nostalgic and surreal dreamscape.

Alongside the photographic work of Takeuchi is the offering from Scottish

YBA artist Anya Gallaccio. Entitled ‘White Ice’, it is sweetly

seductive with a mesmerising shimmering quality. Like a young girl who

has just discovered her mother’s make up, Gallaccio’s piece

doesn’t hold back on making itself thoroughly glam! Although presented

statically onto the gallery wall, as you move around the picture new dimensions

are opened up to the viewers gaze. This illusionary composition at first

appears painterly but beyond its fabricated sparkly foreground lies an

eerie dark foray echoing from underneath. And sitting alongside Takeuchi’s

enigmatic photo-montage these two play teasingly and menacingly well together.

In the upstairs back

room of the gallery Laura White’s bombarding video projection over

collage (‘Dynamo Bi-K’) brings together an entrancing interaction

of video and sculpture. Collage work is always fun to indulge in both

creating and viewing as it allows for a playful altering of things that

are pre-existing. An amalgamation of curious imagery flits across a large

three-dimensional collage array of magazine images and other average consumer

imagery. Courtesy of the Guardian newspaper free-be efforts we find among

White’s work animal stickers familiar to many a Guardian reader!

The delight of this piece is that it works as consumerist regurgitation,

overloaded and spat back. She is the phlegm flogger of the school yard

but not without cause. White is indisputably comparable to being the Hannah

Hoch of the digital video age. The play of her works lies in the relationship

between the image projected, the images projected onto and the combination

that the viewer receives.

Gucci Hoop is about man versus nature. I have incorporated the Gucci fabric

which represents "new" or glamourous or luxurious capitalist

society. The branches are tangled up in the fabric and represent a "old"

natural society, which is where the dreamcatchers come in. The dreamcatchers

are a symbol of Native American mysticism, or religion. The dreamcatcher's

initial intention is to protect people from evil spirits, thoughts and

dreams. Nowadays the symbol is highly commercialized and sold to tourists

as a reminder of an exotic culture which has been mostly lost.

Years later

the precious metal gold caused mass exodus of pioneers into the west towards

the promissed land of California where they might become instantly wealthy.

I use gold in my work to represent the idea of glamour and wealth but

I am also interested in its consequence; a material such as gold may cause

enormous destruction.

Whilst the American artist Sarah Baker presents to us a collage work that

appears like a ship wreak. The piece is entitled ‘Gucci Hoop’

and incorporates fashionable Gucci fabrics that toy with twenty-first

century representations of glamorous capitalist society. The fabrics clutter

a large arrangement of looming tree branches. The branches rise up the

gallery wall and connote a nightmarish Svankmajian Otik-like life of their

own, glammed up in fine Gucci wear. Baker sees these branches as portraying

the originally native American ritual of dreamcatchers and at the same

time belonging to a touristised funked capitalist brutality of commercialising

dreamcatchers!Baker’s mark in the exhibition is of a notable presence

with the impressive scale of her work although she is poorly represented

in the show’s catalogue in relation to her work.

Another American artist appearing here is Doug Fishbone, most famous for

filling Trafalgar Square with 30’000 bananas back in 2005. Fishbone’s

work on display here is similar in tone to both White’s and Baker’s.

Following the principle of taking found images from everyday consumerist

interactions, Fishbone vindictively replays the appropriated images back

out. Using images selected from random Google searches and offered back

through the lesser interactive medium of video, Fishbone provides a flickering

advertising board-esque visual attack of randomness. These seemingly meaningless

images are then coupled with a narrative voice over that tells silly rhymes

about philosophers and ends with the story that is the title piece, ‘Footprints

in the Sand’ (2003). The play of this piece is seen in the relationship

between images and spoken words, the meaning of which proves that efforts

of anti-narratives form narrative. And what could be more nonsensically

Dada?

But it is not all visual play on offer in this show. The typical style of works by Bob and Roberta Smith (aka Patrick Brill) is to make written signs on pieces of found board. But here the Smith’s offering is the world of signs for those who are visually impaired. A found array of boards mounded to the wall of the gallery, as is expected of the Smith’s works, is to be seen without writing. That said though, this work is not to be seen at all, titled as ‘Painting for the Partially Sighted’ (2007) the work encourages to be read through the language of touch. Is this though a giant Braille message or just a cruel hoax? Which ever way one thinks of it this piece is more friendly to the visually impaired that anything else on offer. And why should the blind not be able to indulge in the pleasure of art?

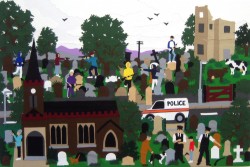

'BB Guns at Law Stand', Paul Caton (2005)

Another artist whose

work you might desire to touch but probably shouldn’t is that of

Paul Caton. His offering in this show is comprised of cut out and collaged

flock backed card that is nostalgic of the 1950’s popular children’s

toy Fuzzy Felts. The Felts were designed to allow small children to create

colourful picturesque depictions of everyday scenes such as farms and

bustling towns using simple flocked backed cut out card shapes. Caton

has taken what is now seen as a sickeningly romanticized out dated views

of happy wholesome white English towns, suburban area and farm lands that

Fuzzy Felts portrayed and has instead created a collage work that embodies

nostalgia with new social trends, such as the social honour of the ASBO

culture.

During the 1990’s production of Fuzzy Felts moved out of Britain

and overseas to the Middle East. The void of which Caton could be said

to be commenting, has worsen the quality of life, creating unemployment

and accounting for more scenes of troubled hooded youth gun culture as

has risen in Britain since the 90’s. Not that Fuzzy Felts can be

entirely blamed for this. As something traditionally child friendly to

play with, the scenes which Caton presents are anything but. Youthful

hooded delinquents run riot with guns through fields, churchyards and

other traditional Fuzzy Felt scenarios! There is something obviously humorous

in Caton’s playful depictions of modern youth culture made to resemble

Fuzzy Felt but at the same time the sub text is frightfully honest.

Peter Harrap exhibits

two paintings in this show that provoke issues of torturous existential

teenage notions that the World is without meaning. ‘When I have

fears’ a new large scaled painting of spray and oil on canvas illustrates

a bored looking teenager within a pseudo glam back drop of acid house

graffiti featuring a sad scrawl of self loathing that reads, ‘When

I have fears that I may cease to be’. These words appear to link

the teenager with the dead and bleeding squirrel in the lower right corner

of the composition. The two together prompt Sartre-esque existential questions

that although dull actually equivocate something of a truly bored teenager

experiencing suffering. The same can be seen and said for his other painting

here, ‘It fluttered and failed to breath’, portraying a melancholic

teenager sat upon a stool, knees curled up to the chest in a protective

gesture looking on, horrified at the side of a dying bird. Harrap’s

paintings though are the unsettling intruder among all these other artists.

His appearance here is unnecessary.

In contrast the upbeat work of Neil Zakiewicz doesn’t fail to bring

back a smile from existentialist misery. Encouraging interactive participation

with a custom made guitar shaped as an over sized painter’s palette

(body) and paint brush (neck). Is it more that mere novelty though? The

guitar is found resting on an easel and plugged into an amplifier hidden

inside a foam board on the wall behind it. The fun in this work is primarily

the aesthetic value, unless you can play like Brian May, but whilst wanting

this to not be just gimmicky, this piece has no more of a pastiche that

being something looking like a palette and brush but is just a guitar.

However, it could be said to connect both visual craftsmanship and painterly

abstraction back together with music but the two were always separate.

It remains though an enjoyable work, offering the chance to trip back

to days of getting teenage kicks. But it isn’t what you play but

more how you play it.

Along with Takeuchi,

Caton and Zakiewicz appears Max Hymes, the fourth BEARSPACE artist representative

in this show. Hymes makes works of sculpture as well as works on paper.

For this collective he has chosen to offer a puzzling situation of items

that among them feature mirrors, the office cabinet and the wooden diamond

appendix shines a sumptuous pineapple at the installations pinnacle. Although

it resembles a pineapple, one can not be sure if it is a pineapple that

actually resides underneath the object’s exterior of brightly coloured

office stationary pins. And from the humorously pseudo-monumental positioning

of the object obscured by elements of routine banality (office pins) one

can begin to see what Hymes’ construction is really getting at.

The ephemera of the pineapple as a consumerist produce and a symbol of

trade and Western colonialism, the modern values that in this self obsessed

image conscious age remains in vanity, admiring one’s self in mirrors

has altered traditional values. Hymes’ work however is not to be

seen as traditionalist but it certainly is inoffensive to old values.

Perhaps overall it is best viewed as a comment on how played down the

colonialist empire of Britain has become. Certainly if this to be the

case, then Hymes’ placement of the mirrors seems to suggest the

viewer reconsider themselves in their reflections of what a garish pin

covered pineapple means to them?

A perfect companion to Hymes’ piece is the monumental book sculpture

work of Jonathan Callan. An amalgamation of various sized books sits solemnly

in the corner of the gallery space. The books spread open are fixed together

thus changing their purpose, destroying their value as containers of text

and re-instating a new text to their presence. The piece is a playful

collage and the re-functioning of pre-existing elements which pronounces

the work creates connotations of grave stones.

The biggest names

in the line up here are the extraordinarily well established pair whose

background needs no explaining. The Chapman Brothers are a modern day

Brothers Grimm and for this show they have opted to present a small scale

work entitled ‘My auntie went to see hell and all I got was this

lousy souvenir’. A title taking grace from a popular t-shirt slogan

culture and at the same time self referencing their other work, the monumental

‘Hell’. The Chapman’s work features miniature nude figures

that are depicted ascending a small mount to over throw a single figure

emblazed with a swastika logo. As the coup rally toward the distinct outsider

their bodies are colliding and morphing into masses of limbs. The fun

in this piece is its devilish charm, the tragic-humour of destruction

that inevitably befalls all who enter into organised systems. Though the

Chapman’s are largely deemed as offensive to millions, there is

nothing overly menacing about the work of two men who nostalgically romanticize

scenes of mutilation like two small boys drawing nasty caricatures of

their teachers! But it is the obvious social commentary that runs through

their works that makes them more that playful big kids and placing them

firmly as quintessentially brazen artists in their own self glorious right.

Another pair whose work has that big kid quality to it is that of Natasha

Kissell and Mark Djiewulski. The duo created a piece that could be mistaken

for an architectural sight model. Entitled ‘The Beast of Bodmin’,

the work is housed in a large glass box obscured by vinyl, forcing the

viewer to gaze inside strategically. On the exterior of the box are a

series of buttons that when engaged with project varying tones of light

on the scenario within. And inside resides a small model building with

a model figure inhabitant. The structure is surrounded by model trees

and a reflective pool covers most of the interior. There is more to this

though that first impression suggest. On closer inspection something surprising

lurks within, a secret frightening element awaits the viewer’s discovery.

Matt Franks’ large scale sculpture, ‘Bellicose Sentinel’ appears to dance in the light at the centre of the gallery space. With its inoffensive Styrofoam rigour the work is reminiscent of Dali and the two prong fork icon of male and female figures. Two tall forks face opposite one another, connected by the addition of a telescope cum giant spray can between the two forks. A whispering sense of domesticity lends itself to the work but the main context of this giant toy like sculpture is the relationship played by the two forks dancing, sexually, together with self awareness of identity and yet an uncertain trauma. Fittingly the work is as dark as others on show here.

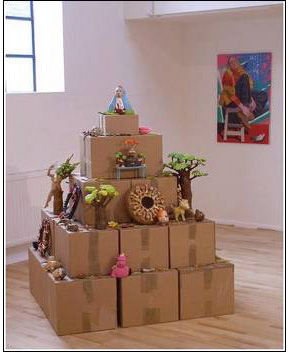

Foreground: 'Discontinued', Jock Mooney (2007)

Background: 'It Fluttered and Failed for Breath', Peter Harrap (2007)

The largest play of images within the show comes from the emerging talent

of recent graduate Jock Mooney. The Scottish artist is a prolific sculpture

and his latest project revealed here for the first time is entitled ‘Discontinued’.

Mooney’s work is characterised by its humorous, anarchic replay

of cultural aspects. This artistic deviant teases the values of mythology,

religions, pop-culture and banalities into twisted garish toy-like sculptures.

A glossy replica of the Virgin Mary sits atop this disposable mockumental

monument whilst images of shitting dogs and worms collides with a transforming

human cum tree character and a series of wreaths among other strange and

random hand sculptured incarnations. Mooney announces on his website

that the concerns of ‘Discontinued’ are “a mound of

cardboard boxes littered with objects - part shrine, part stock room.

Imagery inspired by video nasties, milagros (Spanish term for miracles)

and warped toys nestle amongst souvenir-like tack, with a looming sense

of current day 'horror'”

. Discontinued is seen to be an unfinished work, suggested by the

transitional significance of cardboard boxes as well as the title.

I caught up with Jock shortly after the unveiling of ‘Discontinued’

to find out more about his influences, his aims and being accused of killing

mice! The interview with Jock can be found following this article.

The overall success of this show is the similar collective ethos of rebellion that the artist’s works play out. All, except Harrap, encompass an attitude of defiant fun that make this anarchic gallery offering the prospective upcoming stars they are, soon to be found atop the art market spectrum coaxing in the crowds at the big name venues. Alvarez shares a notion that art is for her about rebellion, she claims “there is a rebellion that has to go on, as galleries and artists we are being very true to contemporary art, in some ways there has to be rebellion.” The distinctive feel of this show is the exciting promise of more to follow.

Interview with Jock Mooney

PAJ - What are the influences completing ‘Discontinued’ ?

JM - The actual shape of cardboard, whenever you make lots of small scale things you can’t just present them on a table, which I have done in the past, you have to find some way of presenting them. At the time I was also making wreath sort of shapes which was based on an idea I had a long time ago visiting a French graveyard which is very different to a British graveyard because they are covered in these ceramic wreaths that are very bright and gaudy and they’ve also got lots of fake flowers all over the place, I really liked that, cause it was quite unexpected cause if u saw fake flowers in a British graveyard you’d kind of think, that’s a bit stingey and a bit tacky isn’t it but also I thought in a way it means they never wilt or die never look awful, that was one of the elements I wanted to bring into it. And also the title ‘discontinued’ came to my head early on when I producing this and shaped then what came after that because it was a word that worked on different levels, discontinued obviously if you look at it very basically is ending something. The way I wanted to use cardboard boxes as a display is vaguely monumental-esque shape, like a memorial, I like the idea of warehouses full of retrieved stock, toys that are withdrawn, discontinued.

PAJ - How to you make the models ?

JM - The models themselves are just made out of a plastic modelling compound. Because in 2004 I started making the work called inventory and there was an opportunity to make work in ceramics and i found the process completed killed any creativity what so ever and it took hours or weeks to make one thing, and I was crap at it as well, which isn’t surprising cause it’s a highly skilled thing to do and so I just got a really cheap tub of moulding material, that drys out, not like clay but weird stuff actually, then painted it with enamel paint and it kind of had a ceramicy looking surface, and it was something that I could make very very quickly, so going from ages and ages making one mould for one fucking thing I sit in an afternoon and just make stuff as it occurred or just make stuff and then play around with stuff so it was quite liberating and that way of working is the way I’ve worked ever since really.

PAJ - What was your work like before you started doing the modelling then ?

JM - Very different. I made a film with a dying mouse in it that got a lot of press attention because it was in an expo and animal rights protesters went all over it and it got in The Sun newspaper. It was at that expo that one of my friends made a felt twin towers with Mickey Mouse flying into it. And I completely separate had a film with a dying mouse in it. So the press really jumped on these two mice things and it got a lot of attention. and there is still a website that you can find it on that has a picture of the twin towers thing and it says that I did it. And its like not my work. Its got a photograph with a caption underneath that says Jock Mooney’s Mickey’s Taliban adventures, but its not actually mine. But the film that I made sparked a lot of controversy because it had a dying mouse in it, which I didn’t kill, I found a mouse that was dying in my stair well, and how do you kill a mouse? and I thought oh I have to put it out of its misery and I couldn’t do it so I filmed it instead which is maybe a little bit more perverse. I think that experience and the subsequent reaction that happened afterwards made me realise if you want to, its not difficult to make shocking, controversial work.

PAJ - Whose work most influences you? We’ve talked about how cultural influences come into your work but is there an artist particularly?

JM - I like Claus Oldenberg a lot, his big big sculptures don’t necessarily appeal to me a lot but I do like them, I prefer his drawings because I think they’re got a lot more interesting, they make you use your imagination a lot more, and the small scale stuff that I do, in a big macho kind of sculptural environment you always get people saying “so, is this a maquette?” and you go “ well, No!” and I quite often prefer peoples models for things that the actual finished thing. Claus Oldenberg drawing of a lipstick in Piccadilly Circus, even if scruffily done, I think is a lot more interesting that seeing, even though its not there, BAM ! Something that’s just been plonked there and that’s it, because that’s not using your imagination as much.

PAJ – Your work has a gory factor and often that can be misconceived as miserable but this piece is enjoyable and fun, although gory in appearance there is something underneath that which is humorous.

JM - I think within the wreath things I liked, there is one wreath that is quite close to a real wreath. Its got flowers and leaves on it, there is one that is the complete polar opposite, its got skulls on it, quite unashamedly basic but like a real wreath, rather than glossing over what death is or going here it is, but its all circular, I really enjoyed making stuff that was horrible and gory because it was enjoyable and fun and funny, I also quite liked making the severed hands and stuff, its like you’re worst fear of what can happen to you, well, one of the worst things.

PAJ – Can you discuss the significance of the wreath with eggs?

JM - Well that was, I really like fried eggs, not to eat, but just the way that they look, I like dropping in lots of things that people can choose to or not to read as a symbol, something along the lines of the discointuined theme, I think that’s about as discontinued as you can get really, seeing as an egg is obviously a symbol or life and if you fry it, then its “well, that’s that one fucked!”

PAJ - How do you feel about exhibiting abroad?

JM - Well, I’ve only had one proper exhibition abroad that I’ve gone and set up, that was in Lithuania, that was good. Other that that, I’ve had stuff in art fairs through the Vane Gallery, in Newcastle, its not the same as going abroad and putting on a major show or anything.

PAJ - How was the work received in Lithuania? Its quite a British/US/Frence cultural influenced work?

JM - I kind of like to think that I don’t make things from a context of a how a large group of people might see them, I make them on the basis of how one person see them, they can obviously talk about it with someone else but I think the country is neither here nor there. I think there is a kind of Japanese influence in there, loads of toys that influenced it, I think hopefully to an extent it is hopefully quite universal but there is always going to be something if you make a work which hundreds of factors/assets to it, one person notices one thing and another person doesn’t notice at all.

Bibliography

http://www.bearspace.co.uk/explay.html

http://www.jockmooney.com